Each fall, I buy firewood from a local place that sells four different kinds of wood. Knowing how I have an opinion on everything, my friends would tease me. “Is that really necessary,” they’d say. “Four kinds of wood? They all burn, right?” But any good camper, live fire chef, or wood burning stove owner knows that not all woods are equal. Oak burns hot and slow. Birch burns bright. Pine is easy to light. And juniper smells like Christmas. Depending on your needs, mother nature has the wood for you.

Chatting with a friend last week about cooking oils, I realized that edible fats might be next on the list for lost arts. That we have an entire grocery store aisle of oils, but do we know how and why to use them? Could cooking oil be headed to obsolescence?

All Fats Welcome

In my house, the cabinet to the right of the range top is loaded with fats. There are bottles of avocado, sesame, coconut, walnut, and olive oil. Crammed in the cracks are a few small vials of finishing oils, maybe chili and truffle, given to me as gifts.

The top shelf of my refrigerator is cluttered with jars filled with the drippings of previous meals. The hard, chalky block of beef tallow. A fluffy cloud white jar of bacon lard. Smooth, glistening straw colored schmaltz. And a pungent golden layer of duck fat. My mind wanders to the salvaged confit cap from a jar of foie gras recently brought back from France. Goose fat, yum!

When I’m choosing a cooking oil, my brain automatically performs a mental calculus that instantly assesses three essential variables: smoke point, flavor profile, and cost. And over the years, I’ve refined my list to four culinary fats that I use every week. So, I thought I would share with you these daily drivers, my epicurean foundation, and why I simply couldn’t cook without them.

What’s a Smoke Point?

To me, the most important characteristic of a cooking oil is how it….cooks. This has a lot to do with the oil’s smoke point, or the temperature at which fats start to…well…smoke. Molecularly speaking, when oils are heated, their free fatty acids (FFAs) start to break down, oxidize, and turn into gas, (i.e. smoke). This can give off a burnt smell, and impart off flavors to the foods you’re cooking. If you’re someone who reuses their cooking fats (which I highly recommend), exceeding the smoke point can also reduce shelf life, or turn the oil rancid more quickly.

Some delicate fats don’t do well heated up, like unrefined walnut, flaxseed, and pumpkin seed. Most live in the mid-heat saute space. Others can stand up to brutal repeated blast furnace temperatures again and again without giving up a wisp of smoke.

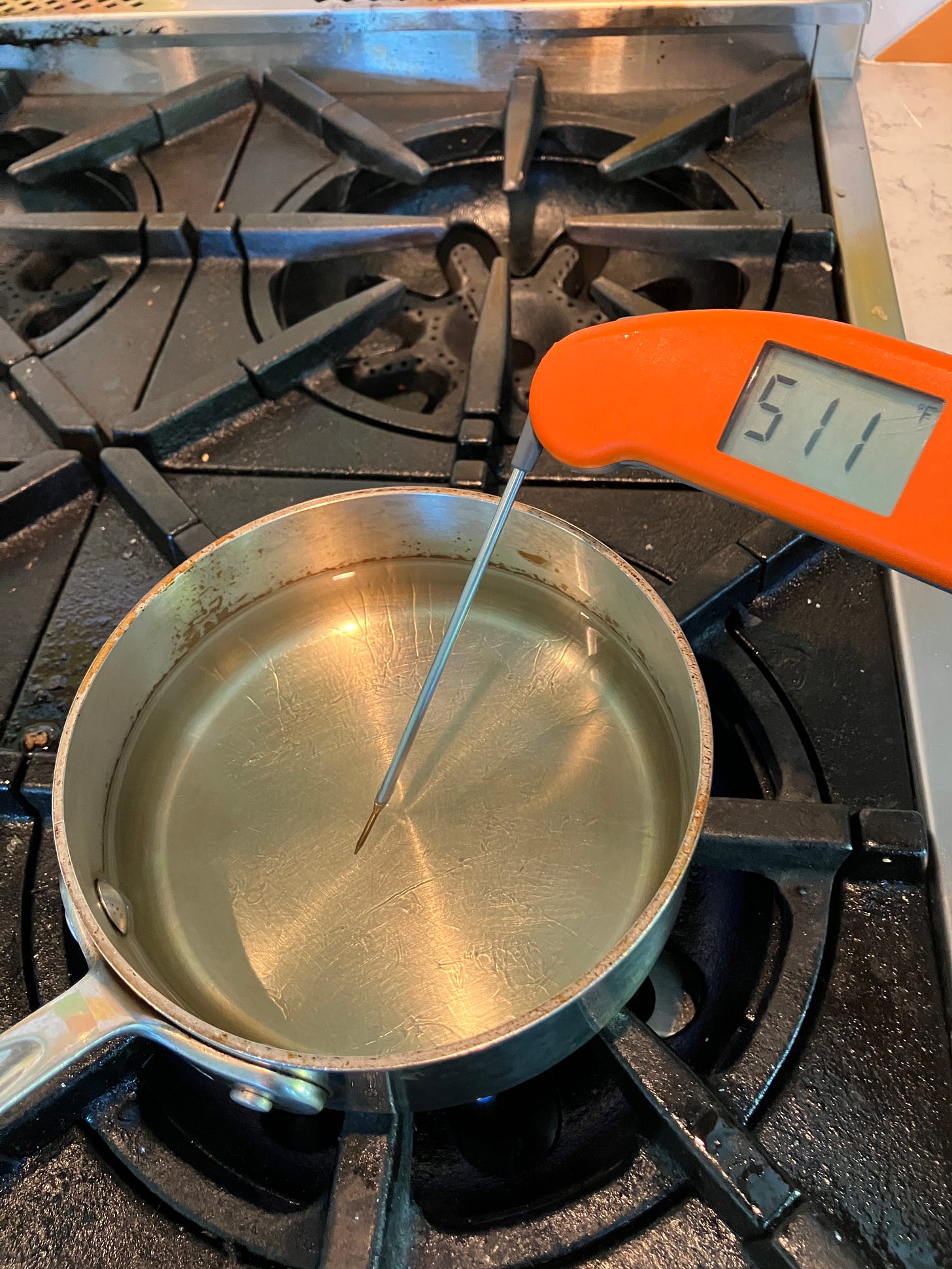

After some research, I found that stated smoke points on the Internet are highly inaccurate, if not completely wrong. I tested two oils on my stovetop: high oleic sunflower oil, and an Italian extra virgin olive oil, both bought at Trader Joe’s. Although the Internet will tell you that most sunflower oils have a smoke point of ~450 degrees, mine got up to 511 before off-gassing. More surprisingly, my EVOO, which traditionally is thought of as a medium smoke point oil (~350 degrees), got up to almost 470 degrees before it started to denature. I’m planning to test a bunch more oils and share my findings later this month, but it appears some oils have a much higher smoke point than the literature lets on.

The Fab Four Fats

So what are the fab four cooking oils that I always keep in my kitchen? Here they are listed in order from most to least used.

Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) is the granddaddy of all oils. Probably the first oil humans cooked with after animal fats. Although the Internet says it starts smoking at 320 degrees, my kitchen tests put the smoke point well above 400 degrees. This means EVOO could hold up to most any cooking application. That said, I still avoid using it for deep frying and grilling as there are cheaper fats for these applications. With its versatility in the kitchen and centuries of documented health benefits, EVOO is a great candidate for being your most frequently used cooking fat. It’s also perfect for uncooked applications like vinaigrettes, sauces, and drizzles. Considering it’s one of the few widely available unrefined oils that are pressed to extract oils rather than chemically extracted (more on that in a future post), it is my go-to fat EVERY DAY! The only downside (if you can call it that), is the EVOO is highly fragrant, and has a fruity taste with a peppery or spicy finish among some varieties. This can clash with foods that have subtle flavors, especially baked goods.

The biggest complaint of EVOO is the cost. This stuff can get crazy expensive. To save some money, buy cheaper stuff for sauteing and frying, and splurge on your favorite high quality oil for uncooked applications like drizzles, salad dressings, and pesto.

Butter: one of my favorite fats–even if it’s been shamed for its cholesterol–butter has a smoke point of 300-350 degrees, which is ideal for sauteing, thickening sauces, and coating veggies or proteins with creamy, sweet goodness. Butter has a harder time with high heat applications (above 350 degrees). That’s because its high moisture content makes butter froth and foam, and its milk solids scorch as they get hotter.

Browning is an additional benefit with butter. Simmer a stick of butter on low heat for 5-7 minutes in a shallow frying pan until foaming subsides. You’ll notice milk solids in the bottom of the pan starting to caramelize. Don’t let these burn! The remaining oil will be light brown in color, and have a delectable nutty fragrance that’s delicious on fish and veggies. Strain the milk solids, and the remaining oil is clarified butter, or Ghee, which brings its smoke point to 450 degrees.

Butter has increased in price over the years, and if you buy organic, grass-fed, it can double the cost. I always buy the cheapest organic butter I can find, and use that for baking and sauteing. The fancy French stuff only gets spread on bread.

Animal Fats (Duck, Schmaltz, Goose, Lard, and Tallow). Gone are the days when most folks cooked with the drippings of yesterday’s meal. But my years as a butcher have taught me the joys of cooking with animal fats. Most have a high smoke point above 375 degrees, with tallow (beef fat) coming in at an astounding 450-500 degrees. These luscious lipids are also chalk full of nutrients missing from chemically refined oils like soybean and canola. In terms of flavor, animal fats beat all other options. Green beans sauteed in schmaltz (chicken fat), or fingerlings roasted in duck fat can only be described as religious experiences. A tablespoon of lard (pork fat) folded into a can of refried beans transports me to my favorite Mexican restaurant. A scoop of bacon fat in my soffritto offers an unctuous, smoky surprise. Floating a chunk of tallow over the grates of the BBQ keeps things from sticking, and adds a beefy boost.

What about the health concerns, you ask? You can go down the cholesterol clinical data rabbit hole, or read published studies that challenge the status quo. I just live by the Enlightened Omnivore motto, “everything in moderation.” Regardless, animal fats are higher in cholesterol, and higher in nutritional value than any other fat. Anecdotally, when I substitute animal fat for other cooking oils, I find I use less of it, and actually feel more full after eating it. Go figure.

The greater challenge is finding these lipids at the store. Folks don’t buy lard like they used to. But that’s ok. If you buy animal proteins, you can make your own animal fats at home. Always save your chicken or duck skin. Take the raw and cooked pork and beef fat you didn’t eat, and put it aside. When you have a pound of the stuff, grind it up in a meat grinder, or give it a good fine chop and add it to a pot with a tablespoon of water over low flame to render. Within minutes, you’ll have golden goodness that you can pour into a jar or ice cube tray to save for later.

Extra Thought: because many chemicals and impurities accumulate in fatty tissues, it’s best to buy the cleanest animals you can afford when harvesting fat. Antibiotic-free, organic, pasture-raised, grass-fed, or barley-fed (in the case of pork) are your best bets.

Organic, High Oleic Sunflower Oil is the only “vegetable” oil I use. It has a smoke point above 500 (I confirmed myself), is void of any flavor or aroma, and costs about four bucks a liter. I use it for baking, Asian cooking, deep frying, popcorn, and anything else that needs high heat and a neutral flavor. I avoid canola and soybean oil even though they have similar characteristics because they’re often extracted with harsh chemicals called hexanes. This also strips them of most nutritional value. Most other seed oils like sunflower, safflower and corn are exposed to the same toxic solvents. But not organic! The USDA only considers chemical-free pressed extraction methods for the organic label. And high oleic strains of sunflower oil are loaded with extra nutrients and health benefits. I don’t always buy organic at the grocery store, but I never make an exception when it comes to seed oils.

Honorable Mentions

There are a few oils that I don’t regularly use, but appreciate their benefit. Some of these are in my pantry right now, and others are very popular among my closest friends..

Coconut and Peanut oil have important roles in cooking. In their unrefined formulations, they are fragrant and impart wonderful flavors that work well with Asian dishes and veggies. For example, I love sauteing brussel sprouts in unrefined coconut oil. I also used to deep fry exclusively in refined peanut oil because of its exceptionally high smoke point. But after reading more about the chemically intensive refining process, I’ve switched to my organic high oleic sunflower oil instead and haven’t noticed any issues. Look for an organic peanut oil if you prefer it.

Avocado Oil holds the smoke point top spot at 480-510 degrees. That’s even higher than beef tallow. It also has lots of purported health benefits, and a light but pleasing taste and smell. Some folks swear by avocado oil, and use it like I do EVOO, putting it on EVERYTHING. No judgment. It’s just not cheap, and I find the stuff cost prohibitive when cooking for a family of five.

Extra Thought: when cooking with a lot of oil, or when using a deep fryer, don’t mix oil type, and never throw out your leftover fats. Let the oil cool, filter out any solids with cheese cloth or fine wire mesh, and then pour the remainder into a heat resistant container (old wine bottles work great). Only fill the bottle halfway, topping it off with new, unused oil of the same type. This extends the life of your oil significantly, and reduces the chance of off flavors or the oil going rancid.

Rendered Thoughts

In the end, selecting the right cooking oil is equal parts food science and culinary magic. But, don’t take it too seriously, and let’s not become so rigid in our food ways that we can’t learn new things from each other. I never knew I could make popcorn with olive oil until I had no other options. The result was a new favorite. So, I’m all ears for corrections and suggestions. Much like the different woods for a fire, the variety of oils in your kitchen is a testament to the diverse and delicious possibilities that await. So, let your culinary adventure begin, and may your pantry be as rich and varied as the meals you create!

So many questions answered yet so many more generated. Ever once in awhile I read that olive oil shouldn’t be heated. What’s up with that? Barley-fed pork? Why? Doesn’t that conflict with article about Las Vegas pork? Also consider oxidation of oils.

What a satisfying article. I learned a lot and I consider myself to be a bit of an oil snob. I appreciate you breaking these fats down for us. So much satiating information. You rock man! 🤘🏼🫒 ~Bryan (Los Angeles, CA)