I hope everyone is enjoying the day off with some food, drink and friendly conversation. I recently had the chance to reread Adrian Miller’s book, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue. and thought how fitting it was for a July Fourth post. If you don’t have plans today, get a copy, a beer and some beef, and enjoy a historically accurate Independence Day.

Also, keep an eye out this weekend for my newest podcast! This month, I get to speak with agriculture policy guru Austin Frerick about his book, Barons: Money, Power, and the Corporation of America’s Food Industry. He’s got a lot to say about the American food system, including how he thinks we should scrap the USDA for parts! Really excited to share our conversation in a few more days.

Be safe and have a great Fourths of July.

One Nation Under ‘Cue

Barbeque is a sacred tradition in America. In fact, some folks are probably already judging me by how I just spelled it.

But even if you’re a novice, you probably know that American Barbecue originated in the South. And no matter how you spell it, (BBQ, Bar-B-Q, barbeque, or barbecue) grilling or roasting meat over an open flame is so irrevocably united with the Fourth of July that it could never be torn asunder. Right?

But did you know that African Americans, and more specifically Jim Crow-oppressed Southern Blacks, saved the July 4th Barbecue from disappearing into historical obscurity?

First, let me confirm that I’m no expert on this subject, but I have read the works of James Beard award-winning Soul Food Scholar, Adrian Miller, and certified master barbecue judge, Joseph Haynes. They know their stuff when it comes to BBQ. And as I make smash burgers for 50 of my closest friends tomorrow, I will be thinking about what these two authors have to say about the original pit bosses of the Fourth of July Barbecue tradition, African Americans.

Let’s Start from the Beginning

Cooking meat as celebration has been part of North American history long before Europeans or Africans arrived here. Native Americans were the first BBQers, and their cooking history is a rich one (check out The Sioux Chef). When Europeans arrived in Virginia, they were exposed to the BBQ techniques of the local Powhatan Tribe. Soon, the concept of barbecue became a “melting pit” (wish I could claim that, but it’s Miller’s phrase), of Indigenous, Caribbean, African and European influences. Even the name, barbacoa, is a blend of Arawak, Spanish, and English.

One thing in common with all barbecuing traditions is that it has always been a community affair. People love to grill their meat in groups. And those groups just kept getting bigger. From the 16th to 18th Centuries, B-B-Qing in the Southern colonies of America evolved from small family or village celebrations into larger civic, church, and political picnics; and then after US independence, all-out statewide festivals sometimes feeding more than 10,000 people.

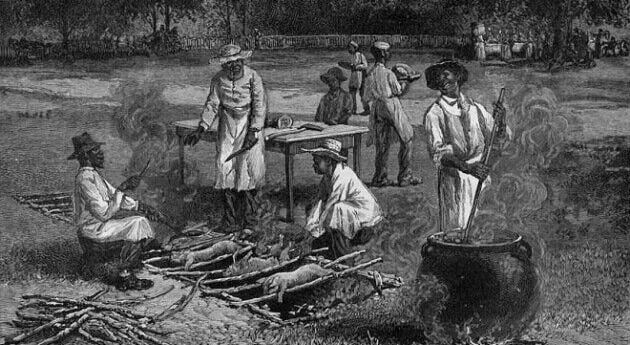

The cooking method of choice back then was the OG “low and slow,” a large pit with red-hot coals and a few sticks to flip the meat. Although pork is more commonly the barbecue protein of choice these days, back then, it could have just as easily been lamb, beef, raccoon, beaver or opossum. The sauce was a base of vinegar and red peppers; no doubt influences from Africa and the Caribbean. Over time, tomatoes, sugar, and mustard also seeped into the recipe.

What most folks forget was that although wealthy, white men were the hosts of this meat merrymaking, the laborious, all-day, back-breaking work required to feed thousands of celebrating Southerners was predominantly endured by African Americans, most of whom were slaves.

These slaves weren’t only providing elbow grease. African Americans were true masters of the craft. In fact, Miller asserts that African American participation was essential for the process to even be considered true barbecue. For some whites, “what distinguished a barbecue from a bunch of adequately cooked meat seemed to be the involvement of African Americans.” Recipes, iconography, and photographs depicted African Americans owning an almost secret BBQ process.

Barbecue and Independence Day

The Declaration of Independence might have happened in 1776, but it wasn’t until after the Revolutionary War in 1783, that celebrating the Fourth of July with BBQ really took off. There were huge Independence Day BBQs as far north as Yankee Philadelphia (1788), as far East as Paris where Thomas Jefferson hosted an expat barbecue dinner (1789), and as far West as Wisconsin—then just a fur trading territory (1791). For decades after, BBQ festivals were organized on the Fourth of July across the country, and especially in the South. That is until celebrations came to a dramatic hiatus when the first shots were fired at Ft. Sumter in 1861, marking the beginning of the American Civil War.

It’s probably not surprising that for a long time after the Civil War, Southerners were less interested in celebrating the 4th of July. Independence Day Bar-B-Qs all but disappeared from public calendars. It looked like the Independence Day Barbecue was on the path to extinction.

Lucky for us, Southern Blacks transformed July 4th into a celebration of their newly found freedom. In 1901, the Atlanta Constitution reported, “[T]he [Fourth of July] is here, as in most places in the South, given over to the Negroes, who celebrate [it] in truly royal fashion.” For the next century, Independence Day became an almost exclusively African American holiday in the states of the former Confederacy.

It wasn’t until the 1950s with the mass-produced Weber Kettle Grill and Cold War Patriotism that the Independence Day BBQ became a popular choice once again among White Southern Americans, and all Americans in general.

Today’s Fourth of July ‘Cue

Today, from a culinary perspective, I feel like the pendulum is swinging back towards the middle, somewhere between Southern pulled pork or smoked brisket and hot dogs and hamburgers. And quite honestly, I feel like we might have the best of both worlds, at least in terms of food. I’d love to know what’s on your July Fourth Menu, or better yet, share some pics of your table spreads if you get the chance, and I’ll put them up on social media.

In terms of celebrating the themes of the Fourth of July, well I can also appreciate and reflect on how rich and complicated our American History really is. Maybe our food heritage can teach us all a little bit about diversity and inclusion.

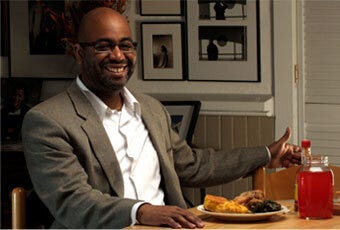

Adrian Miller said it best in his book when talking about how he likes to party on July 4th.

“For me, [the Fourth of July is] about celebrating with friends, family, and loved ones. It’s also a chance to pause and reflect on what it means to “celebrate” a nation that still falls short of its promise, but one that I call home. I live in the country that I love, and I want it to be better. Perhaps having diverse people sitting at a table and enjoying barbecue in all of its glorious forms, even kosher and “vegan,” and respectfully discussing the issues of the day can be a first step to a more perfect union.”

Amen to that!

Happy Fourth of July to all of you!

I wanted to offer a special thanks to everyone for your continued support of Enlightened Omnivore. If you haven’t already, please consider following me on Facebook and Instagram,

Keep an eye out this weekend for my newest podcast with Austin Frerick, who has a lot to say about his book, Barons: Money, Power, and the Corporation of America’s Food Industry. If you missed last month’s podcast, check out The Magic of Mushrooms with Mycologist, Rachel Linzer.